MLegS Tutorial 03: Spectral Transformation

Disclaimer: This MLegS tutorial assumes a Linux or other Unix-based environment that supports bash terminal commands. If you are using Windows, consider installing the Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL).

In this tutorial, you will learn how MLegS converts between the physical representation of a scalar field and its spectral coefficient representation. A scalar field defined in a radially unbounded domain can be expressed either in its original (physical) form in cylindrical coordinates \( (r, \phi, z) \) at discretized collocation points, referred to as the physical space expression, or as a set of spectral basis function coefficients, referred to as the spectral space expression. A backward spectral transformation refers to obtaining the physical space expression from the spectral one, while a forward spectral transformation involves computing the spectral space expression when the physical form of the scalar is known.

Given no aliasing or undersampling errors, these two expressions should represent the same scalar data. Using a data type structure scalar, MLegS provides these two-way spectral transformation subroutines, enabling further operations in either spectral or physical spaces. This tutorial will guide you through the following steps:

- Learn the Data Type Structure of

scalar- Understand how

scalarstores both physical and spectral space representations, enabling conversions between these forms. - Review the interal structures of

scalar, such as an array for physical values at collocation points and for spectral coefficients.

- Understand how

- Perform the Backward Spectral Transformation

- Use MLegS’s built-in subroutines,

trans(), to perform the backward spectral transformation. - This translates spectral coefficient data into values in the cylindrical coordinate system at discretized collocation points.

- Use MLegS’s built-in subroutines,

- Perform the Forward Spectral Transformation

- Discover how to convert a scalar field from its physical space expression to spectral coefficients.

Completing this tutorial will equip you with a foundational understanding of how to use MLegS’s spectral transformation capabilities to transition between physical and spectral representations of scalar fields.

Table of Contents

- MLegS Tutorial 03: Spectral Transformation

Learn the Data Type Structure of scalar

MLegS includes a built-in data type scalar to facilitate mathematical operations on a scalar function in either spectral or physical spaces. This data type is essentially a 3-dimensional array with additional labels and parameters to indicate how spectral transformations are applied to the scalar field. Given a scalar variable s, its internal structure is as follows:

| Elements | Type | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

s%glb_sz(3) | integer | unassigned | Global sizes of the scalar array \( (r, \phi, z) \) |

s%loc_sz(3) | integer | unassigned | Local sizes of the distributed scalar array \( (r, \phi, z) \) |

s%loc_st(3) | integer | unassigned | Local starting indices of the distributed scalar array \( (r, \phi, z) \) |

s%axis_comm(3) | integer | unassigned | MPI processor distribution status |

s%e(:,:,:) | complex (ptr) | unassigned | Scalar array data |

s%ln | real | 0.D0 | Logarithmic term coefficient (almost always zero except for uncommon scalar fields not decaying to zero as \( r \rightarrow \infty \)) |

s%nrchop_offset | integer | 0 | Truncation index offset in the \( r \) direction for forward transformation in \( r \) |

s%npchop_offset | integer | 0 | Truncation index offset in the \( \phi \) direction for forward transformation in \( \phi \) |

s%nzchop_offset | integer | 0 | Truncation index offset in the \( z \) direction for forward transformation in \( z \) |

s%space | character*3 | unassigned | Current representation of e(:,:,:) ('PPP' for physical space, 'FFF' for spectral space) |

Unless using single-core execution, the data in s%e(:,:,:) are distributed across multiple MPI processors, allowing parallel operations at different locations. First, let’s explore the global configuration of the scalar array in physical and spectral spaces, assuming a single-core execution.

Global Data Configuration of scalar

The global configuration of the array in scalar appears as follows:

Physical Space Form

For a given k, s%e([rows],[cols],k) when s%space = 'PPP' stores the scalar function values \( s(r_i, \phi_j, z_k) \) at \( z = z_\kappa \) as follows:

| Col 1’s real part | Col 1’s imag part | Col 2’s real part | Col 2’s imag part | \( \cdots \) | Col \( NP/2 \)’s real part | Col \( NP/2 \)’s imag part | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row 1 | \( s(r_1, \phi_1, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_1, \phi_2, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_1, \phi_3, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_1, \phi_4, z_\kappa) \) | \( \cdots \) | \( s(r_1, \phi_{NP-1}, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_1, \phi_{NP}, z_\kappa) \) |

| Row 2 | \( s(r_2, \phi_1, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_2, \phi_2, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_2, \phi_3, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_2, \phi_4, z_\kappa) \) | \( \cdots \) | \( s(r_2, \phi_{NP-1}, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_2, \phi_{NP}, z_\kappa) \) |

| Row 3 | \( s(r_3, \phi_1, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_3, \phi_2, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_3, \phi_3, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_3, \phi_4, z_\kappa) \) | \( \cdots \) | \( s(r_3, \phi_{NP-1}, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_3, \phi_{NP}, z_\kappa) \) |

| \( \vdots \) | \( \vdots \) | \( \vdots \) | \( \vdots \) | \( \vdots \) | \( \ddots \) | \( \vdots \) | \( \vdots \) |

| Row \( NR \) | \( s(r_{NR}, \phi_1, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_{NR}, \phi_2, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_{NR}, \phi_3, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_{NR}, \phi_4, z_\kappa) \) | \( \cdots \) | \( s(r_{NR}, \phi_{NP-1}, z_\kappa) \) | \( s(r_{NR}, \phi_{NP}, z_\kappa) \) |

Since \( s(r,\phi,z) \), which is assumed to be real-valued, is stored in s%e(:,:,:), which is the complex data type, each entry can store two \( \phi \)-collocation point values. For each k from 1 to \( NZ \), this \( \kappa \)-th slice represents the scalar’s physical information at \( z = z_\kappa \). Therefore, all \( NR \times NP/2 \times NZ \) entries actively store the scalar data.

Spectral Space Form

For a given k, s%e([rows],[cols],k) when s%space = 'FFF' stores the spectral coefficients \( s_n^{m\kappa} \) at a fixed \( \kappa \) as follows:

| Col 1 | Col 2 | Col 3 | \( \cdots \) | Col \( NPCHOP \) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row 1 | \( s_{0}^{0\kappa} \) | \( s_{1}^{1\kappa} \) | \( s_{2}^{2\kappa} \) | \( \cdots \) | \( s_{NPCHOP-1}^{(NPCHOP-1)\kappa} \) |

| Row 2 | \( s_{1}^{0\kappa} \) | \( s_{2}^{1\kappa} \) | \( s_{3}^{2\kappa} \) | \( \cdots \) | \( s_{NPCHOP}^{(NPCHOP-1)\kappa} \) |

| \( \vdots \) | \( \vdots \) | \( \vdots \) | \( \vdots \) | \( \cdots \) | \( \vdots \) |

| Row \( NRCHOP-NPCHOP+1 \) | \( s_{NRCHOP-NPCHOP}^{0\kappa} \) | \( s_{NRCHOP-NPCHOP+1}^{1\kappa} \) | \( s_{NRCHOP-NPCHOP+2}^{2\kappa} \) | \( \cdots \) | \( s_{NRCHOP-1}^{(NPCHOP-1)\kappa} \) |

| \( \vdots \) | \( \vdots \) | \( \vdots \) | \( \vdots \) | \( ⋰ \) | - |

| Row \( NRCHOP-2 \) | \( s_{NRCHOP-3}^{0\kappa} \) | \( s_{NRCHOP-2}^{1\kappa} \) | \( s_{NRCHOP-1}^{2\kappa} \) | \( \cdots \) | - |

| Row \( NRCHOP-1 \) | \( s_{NRCHOP-2}^{0\kappa} \) | \( s_{NRCHOP-1}^{1\kappa} \) | - | \( \cdots \) | - |

| Row \( NRCHOP \) | \( s_{NRCHOP-1}^{0\kappa} \) | - | - | \( \cdots \) | - |

Note that the entry at Row \( (i+1) \) and Column \( (j+1) \) stores the spectral coefficient \( s_{i+j}^{j\kappa} \) if it is not truncated. Since the scalar is real-valued, the negative part of \( m \) is solely the complex conjugate of its positive counterpart and therefore does not need to be stored. In the axial direction, the total size of the array remains \( NZ \). However, the first \( 1,2,\cdots, NZCHOP \) array slices store the spectral coefficient information at \( \kappa = 0,1, \cdots, NZCHOP-1 \), while the last \( NZ, NZ-1, \cdots, NZ-NZCHOP+3 \) array slices store the spectral coefficient information at \( \kappa = -1, -2, \cdots, -NZCHOP+2 \). All intermediate slices between \( \kappa = NZCHOP+1 \) and \( \kappa = NZ-NZCHOP+2 \) are inactive. The spectral truncation parameters—\( NRCHOP \), \( NPCHOP \), and \( NZCHOP \)—follow the global setup unless the offset parameters s%nrchop_offset, s%npchop_offset, and s%nzchop_offset are specified as nonzero integers.

Storage Size

The total global storage size of s%e(:,:,:) is determined during the spectral transformation kit initialization stage through the parameters tfm%nrdim, tfm%npdim, and tfm%nzdim. These size parameters are set to accommodate all active entries in both physical and spectral cases, with extra entries to account for potential truncation offsets.

After declaring a scalar variable s, it should be initialized using the following commands:

!# Fortran

! ... declaration block

integer(i4), dimension(3) :: glb_sz

type(scalar) :: s

! ... after the spectral transformation kit (tfm) initialization

glb_sz = (/ tfm%nrdim, tfm%npdim, tfm%nzdim /)

call s%init(glb_sz, (/ 0, 1, 2 /)); s%space = 'FFF'

Now s%glb_sz is assigned (/ tfm%nrdim, tfm%npdim, tfm%nzdim /). The second parameter in s%init() specifies the local data distribution and is assigned to s%axis_comm. This parameter is explained in the following section.

Local Data Distribution of scalar

General Procedure

To utilize MPI parallelism in scalar transformations and further operations, such as the Laplacian, global data is decomposed and locally distributed to each MPI processor’s memory. MLegS employs an in-house pencil decomposition scheme (similar to Laizet & Li, 20111), with the general procedure as follows:

- Arrange MPI Workers in a 2-Dimensional Cartesian Coordinate Topology

- For example, with 6 processors of ranks 0 through 5, the processors are arranged in a 3-by-2 grid and assigned 2-dimensional coordinates: (0, 0), (0, 1), (1, 0), (1, 1), (2, 0), and (2, 1).

- This MPI communicator toplogy setup is done during the program initialization stage: see

set_comm_groups().

- Decompose Two Global Array Dimensions for Local Distribution to MPI Workers

- The first array dimension is divided into 3 parts along processor dimension 1 (i.e., [0–2], *), while the second array dimension is divided into 2 parts along processor dimension 2 (*, [0–1]).

- Retain One Array Dimension Residing Locally in Every Processor

- The remaining array dimension is not decomposed and fully resides locally in every processor, allowing spectral transformations and operations to be performed along this dimension.

- Redistribute Local Array Dimensions as Needed

- When a different array dimension needs to reside locally, the MPI workers exchange data with each other to redistribute the arrays, ensuring the required dimension is locally available for operations.

The second parameter in s%init(), consisting of the ordered integers 0, 1, and 2, determines which array dimension initially resides locally in MPI processors and how the other two dimensions are distributed:

- The first, second, and third entries correspond to the radial (first), azimuthal (second), and axial (third) dimensions of the scalar data array

s%e(:,:,:), respectively. - For each entry:

- Integer 0: Indicates that the corresponding array dimension is not decomposed and fully resides locally.

- Integer 1: Indicates that the corresponding array dimension is decomposed along Cartesian processor dimension 1.

- Integer 2: Indicates that the corresponding array dimension is decomposed along Cartesian processor dimension 2.

Therefore, in the above scalar initialization, the second parameter input of (/ 0, 1, 2 /), assigned to s%axis_comm, places the radial (first) dimension of the scalar array locally in every processor, while the azimuthal (second) and axial (third) dimensions are decomposed along Cartesian processor dimensions 1 and 2, respectively.

The decomposition scheme, applied during the preceding initialization stages, is executed by running the following command:

!# Fortran

! ... declaration block

integer(i4), dimension(3) :: glb_sz

complex(p8), dimension(:,:,:), allocatable :: array_glb

type(scalar) :: s

! ... after the spectral transformation kit (tfm) initialization

glb_sz = (/ tfm%nrdim, tfm%npdim, tfm%nzdim /)

call s%init(glb_sz, (/ 0, 1, 2 /)); s%space = 'FFF'

allocate(array_glb(glb_sz(1), glb_sz(2), glb_sz(3))

array_glb = 0.D0 + iu*0.D0

! /* assign spectral coeff. values to glb_sz /* !

! Here, s%disassemble() performs the pencil decomposition

call s%disassemble(array_glb);

Slab Decomposition for 2-Dimensional Data

This approach also supports a slab decomposition scheme for 2-dimensional data cases (i.e., \( NZ = 1 \)), by setting the processor topology as (# of MPI processors)-by-1 and assigning the array’s third dimension (of size 1) to Cartesian processor dimension 2 (of size 1, as well), which de facto does nothing. This tutorial’s accompanying Fortran programs, backward_trans and forward_trans, actually use this approach as they deal with 2D data.

Perform the Backward Spectral Transformation

Now that you understand how scalar is designed in MLegS, let’s perform the backward spectral transformation using the tutorial program backward_trans.f90.

The program sets up a scalar variable s in the FFF space, where values are assigned as shown below:

!# Fortran

! ...

glb_sz = (/ tfm%nrdim, tfm%npdim, tfm%nzdim /)

allocate(array_glb(glb_sz(1), glb_sz(2), glb_sz(3)))

array_glb = 0.D0 ! all coefficients are zero ...

array_glb(2, 2, 1) = 1.D0; array_glb(2, 3, 1) = 1.D0 ! but these two. What spectral elements correspond to these?

call s%init(glb_sz, (/ 0, 1, 2 /))

s%space = 'FFF'

call s%disassemble(array_glb)

s is then transformed to the physical space, where s%space becomes 'PPP', and s%e stores the scalar field values at the collocation points:

!# Fortran

call trans(s, 'PPP', tfm) ! scalar s must be originally in the FFF space

The scalar data in spectral space, before the backward transformation, is stored in [root_dir]/output/dat/scalar_FFF_original.dat, while the data in physical space, after the transformation, is stored in [root_dir]/output/dat/scalar_PPP.dat. The corresponding \( r \) and \( \phi \) coordinates (collocation points) are saved in [root_dir]/output/dat/coords_r.dat and [root_dir]/output/dat/coords_p.dat, respectively.

#! bash

cd ../ # Navigate to the root directory, assuming the terminal is opened in the default directory ([root_dir]/tutorials/).

# Do program compilation. You will be able to see what actually this Makefile command runs in the output.

make backward_trans

#! bash

# get the total number of processors of your system

np=$(nproc) # if your system can access more than 32 processors, set np <= 32.

echo "The system's total number of processors is $np"

# run the program with your system's full multi-core capacity.

mpirun.openmpi -n $np ./build/bin/backward_trans

# # for ifx + IntelMPI

# mpiexec -n $np ./build/bin/backward_trans

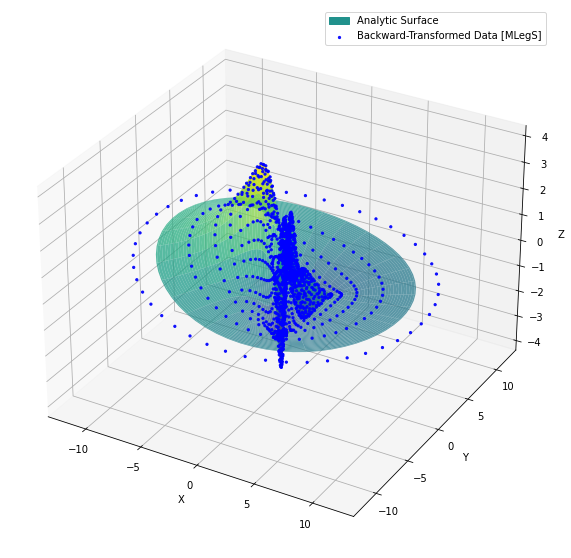

Looking into the code, you can see that the scalar field has only two nonzero spectral coefficients, \( s_2^{10} \) and \( s_3^{20} \), both set to unity. Therefore, the scalar s represents the following scalar field:

where \( c.c. \) denotes the complex conjugate of the preceding term, which is included to ensure that the scalar field is real-valued. In input_2d.params, \( L \) is set to 1, and \( P_{L_2}^1 (r) \) and \( P_{L_3}^2 (r) \) for \( L = 1 \) are given by (Matsushima & Marcus, 19972)):

The multiplication factors next to the \( \times \) symbol normalize the mapped Legendre functions to order unity (Lee & Marcus, 20233). Therefore, the exact form of \( s(r,\phi) \) is:

\[s(r,\phi) = 2 \left[ \sqrt{\frac{5}{12}} \cdot \frac{-6 r(r^2 - 1)}{(r^2 + 1 )^2} \cos (\phi) + \sqrt{\frac{7}{240}} \cdot \frac{60 r^2(r^2 - 1)}{(r^2 + 1 )^3} \cos (2 \phi) \right],\]where the factor of 2 accounts for \( c.c. \). Using the matplotlib code provided below, you can verify that the backward-transformed data from MLegS ([root_dir]/output/dat/scalar_PPP.dat) correctly reconstructs the physical representation of s with no error.

#! Python3

# to run this cell, install sympy, numpy and matplotlib in your Python3 environment.

import sympy as sp

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.patches as mpatches

# Symbolically declare the analytically exact scalar field

r, phi = sp.symbols('r phi')

f = 2 * ((2 * np.math.factorial(2+1) / (2*2 + 1))**(-0.5) * -6 * r * (r**2 - 1) / (r**2 + 1)**2 * sp.cos(phi) \

+ (2 * np.math.factorial(3+2) / (2*3 + 1))**(-0.5) * 60 * r**2 * (r**2 - 1) / (r**2 + 1)**3 * sp.cos(2 * phi))

# 2 * ( ... ) is due to the addition of c.c.

# Generate analytic scalar data for the plot

f_num = sp.lambdify((r, phi), f)

r_vals = np.linspace(0, 10, 100)

phi_vals = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi, 64)

R, Phi = np.meshgrid(r_vals, phi_vals)

X = R * np.cos(Phi)

Y = R * np.sin(Phi)

Z = f_num(R, Phi)

# Load MLegS data

NR = 32; NP = 48

f_val = np.loadtxt('../output/dat/scalar_PPP.dat', skiprows=1, max_rows=NR)

coords_r = np.loadtxt('../output/dat/coords_r.dat', skiprows=1, max_rows=NR)

coords_p = np.loadtxt('../output/dat/coords_p.dat', skiprows=1, max_rows=NP)

X_d = []; Y_d = []; Z_d = []

for index, value in np.ndenumerate(f_val[:NR-1, :NP]):

X_d.append(coords_r[index[0]] * np.cos(coords_p[index[1]]))

Y_d.append(coords_r[index[0]] * np.sin(coords_p[index[1]]))

Z_d.append(value)

# Create the 3D plot

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10, 10))

ax = fig.add_subplot(projection='3d')

# Plot the surface

surf = ax.plot_surface(X, Y, Z, cmap='viridis', alpha=0.75)

# Create a custom legend entry for the surface

surface_patch = mpatches.Patch(color=plt.cm.viridis(0.5), label='Analytic Surface [MLegS]')

# Scatter plot of MLegS data

scatter_plot = ax.scatter(X_d, Y_d, Z_d, s=5, c='b', marker='o', alpha=0.9, label='Backward-Transformed Data [MLegS]')

# Set labels and add legend

ax.set_xlabel('X')

ax.set_ylabel('Y')

ax.set_zlabel('Z')

ax.legend(handles=[surface_patch, scatter_plot], labels=['Analytic Surface [MLegS]', 'Backward-Transformed Data [MLegS]'])

plt.show()

In general, the backward transformation of a scalar in spectral space takes the following steps:

- Backward Fourier Transformation in \( \phi \): From

'FFF'to'FPF' - Change the Locally Residing Array Dimension: From \( \phi \) to \( r \)

- Backward Mapped Legendre Transforamtion: From

'FPF'to'PPF'(For 2-Dimensional Arrays,'PPF'is the same as'PPP') - (For 3-Dimensional Arrays) Change the Locally Residing Array Dimension: From \( r \) to \( z \)

- (For 3-Dimensional Arrays) Backward Fourier Transforamtion in \( z\): From

'PPF'to'PPP'

Perform the Forward Spectral Transformation

To verify that the forward spectral transformation recovers the spectral space form of the backward-transformed scalar, we will use the tutorial program forward_trans.f90.

The program loads a scalar variable s in the 'PPP' space from the previous backward_trans run:

!# Fortran

! ...

call s%init(glb_sz, (/ 1, 0, 2 /))

s%space = 'PPP'

call mload(trim(adjustl(LOGDIR)) // 'scalar_PPP.dat', s, is_binary = .false., is_global = .true.)

s is then transformed to the spectral space, where s%space returns to 'FFF', and s%e recovers the spectral coefficient values:

!# Fortran

call trans(s, 'FFF', tfm) ! scalar s must be originally in the PPP space

Let’s compile and run the forward transforamtion tutorial program.

#! bash

cd ../ # Navigate to the root directory, assuming the terminal is opened in the default directory ([root_dir]/tutorials/).

# Do program compilation. You will be able to see what actually this Makefile command runs in the output.

make forward_trans

#! bash

# get the total number of processors of your system

np=$(nproc) # if your system can access more than 32 processors, set np <= 32.

echo "The system's total number of processors is $np"

# run the program with your system's full multi-core capacity.

mpirun.openmpi -n $np ./build/bin/forward_trans

# # for ifx + IntelMPI

# mpiexec -n $np ./build/bin/forward_trans

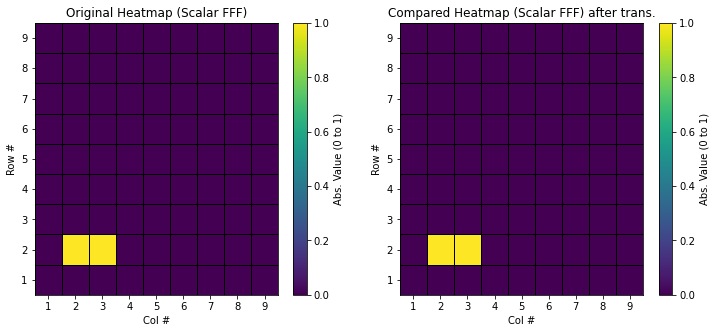

After the forward transformation, the scalar data in spectral space is saved to [root_dir]/output/dat/scalar_FFF.dat. This data should be identical to the original spectral data stored in [root_dir]/output/dat/scalar_original_FFF.dat, where only \( s_2^{10} \) (Row 2, Column 2) and \( s_3^{20} \) (Row 2, Column 3) are unity. Using the matplotlib code provided below, you can validate this identity.

#! Python3

# to run this cell, install numpy and matplotlib in your Python3 environment.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Load MLegS data from files

NRCHOP = 32; NPCHOP = 25

data_original = np.loadtxt('../output/dat/scalar_FFF_original.dat', skiprows=1, max_rows=NRCHOP)

data_compared = np.loadtxt('../output/dat/scalar_FFF.dat', skiprows=1, max_rows=NRCHOP)

# Compute the absolute values of complex numbers from alternating columns

# Separate real and imaginary parts and calculate the magnitude (absolute value)

data_original = np.abs(data_original[:NRCHOP-1, :NPCHOP*2:2] + 1j * data_original[:NRCHOP-1, 1:NPCHOP*2:2])

data_compared = np.abs(data_compared[:NRCHOP-1, :NPCHOP*2:2] + 1j * data_compared[:NRCHOP-1, 1:NPCHOP*2:2])

# Create a figure with two subplots

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 5))

# Set tick labels to start from 1

for i in range(0,2):

axs[i].set_xticks(np.arange(0,10) + 0.5)

axs[i].set_xlabel('Col #')

axs[i].set_xticklabels(np.arange(1,11))

axs[i].set_yticks(np.arange(0,10) + 0.5)

axs[i].set_ylabel('Row #')

axs[i].set_yticklabels(np.arange(1,11))

# Plot original data heatmap

cax1 = axs[0].pcolormesh(data_original[0:9, 0:9], cmap='viridis', edgecolors='black', linewidth=0.5)

axs[0].set_title("Original Heatmap (Scalar FFF)")

fig.colorbar(cax1, ax=axs[0], orientation='vertical', label='Abs. Value (0 to 1)')

# Plot compared data heatmap with dividers

cax2 = axs[1].pcolormesh(data_compared[0:9, 0:9], cmap='viridis', edgecolors='black', linewidth=0.5)

axs[1].set_title("Compared Heatmap (Scalar FFF) after trans.")

fig.colorbar(cax2, ax=axs[1], orientation='vertical', label='Abs. Value (0 to 1)')

# Display the plot

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

In general, the forward transformation of a scalar in spectral space takes the following steps:

- (For 3-Dimensional Arrays) Forward Fourier Transforamtion in \( z\): From

'PPP'to'PPF' - (For 3-Dimensional Arrays) Change the Locally Residing Array Dimension: From \( z \) to \( r \)

- Forward Mapped Legendre Transforamtion: From

'PPF'to'FPF'(For 2-Dimensional Arrays,'PPP'is the same as'PPF') - Change the Locally Residing Array Dimension: From \( r \) to \( \phi \)

- Forward Fourier Transformation in \( \phi \): From

'FPF'to'FFF'

These are exactly the reverse of the backward spectral transformation.

-

Laizet, S., & Li, N. (2011). Incompact3d: A powerful tool to tackle turbulence problems with up to \( O (10^5)\) computational cores. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids, 67(11), 1735–1757. https://doi.org/10.1002/fld.2480 ↩

-

Matsushima, T., & Marcus, P. S. (1997). A spectral method for unbounded domains. Journal of Computational Physics, 137(2), 321–345. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcph.1997.5804 ↩

-

Lee, S., & Marcus, P. S. (2023). Linear stability analysis of wake vortices by a spectral method using mapped Legendre functions. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 967, A2. https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2023.455 ↩